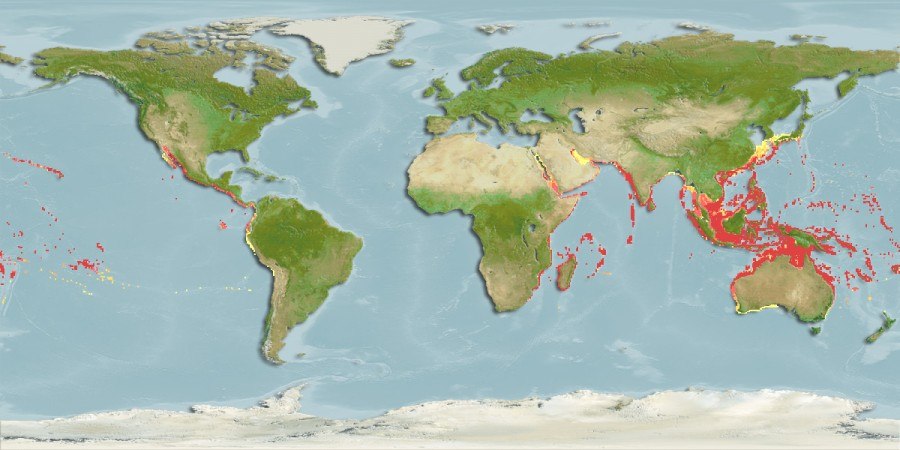

Echinothrix calamaris, commonly known as the banded sea urchin or long-spined sea urchin, is a species of sea urchin belonging to the family Diadematidae. The genus name ‘Echinothrix‘ derives from the Greek ‘echinos‘ meaning ‘hedgehog‘ or ‘sea urchin‘, and ‘thrix‘ meaning ‘hair‘, referring to the long, thin spines of these urchins. This species is found in tropical waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, from the coasts of East Africa to the Pacific Islands, including the Philippines, Indonesia, Australia, and the Great Barrier Reef. It mainly inhabits coral reefs, lagoons, and rocky areas, from the intertidal zones down to depths of approximately 70 meters.

Echinothrix calamaris is a medium-sized sea urchin that can reach up to 5 centimeters in test diameter, excluding its spines. Its most distinctive feature is the extremely long and thin spines, which can grow several times the diameter of its body, reaching lengths of up to 30 centimeters. The spines vary in coloration, ranging from black or dark brown to shades of purple, reddish, or greenish, often with alternating light and dark bands. This sea urchin has two types of spines: long, hollow, and brittle ones used mainly for defense, and shorter, robust, and sharp ones that cover its shell and are used for mobility and substrate manipulation. The long banded spines are arranged in five groups, exhibiting pentaradial symmetry. The shorter spines can range in color from yellow to dark brown. Compared to Echinothrix diadema, another long-spined sea urchin species, Echinothrix calamaris can be distinguished by the presence of short, robust white or translucent spines and the distinctive banding on the long spines. In the Indian Ocean, this species has been described with completely dark coloration, lacking the banded pattern seen in individuals from other regions.

In terms of diet, Echinothrix calamaris is an omnivorous species that is active during the day. At night, it usually hides in crevices. Its diet includes encrusting coralline algae, macroalgae, organic detritus, and small amounts of animal material such as sponges, corals, and other small invertebrates. This urchin uses its specialized mouthparts, known as Aristotle’s lantern, to scrape and grind its food from rocky or coral substrates. By feeding on algae, it helps control excessive algal growth on coral reefs, thus promoting ecosystem health. However, in some areas where natural predators of sea urchins are scarce, Echinothrix calamaris may contribute to coral erosion by feeding on encrusting algae on coral surfaces.

The reproduction of Echinothrix calamaris is sexual and occurs through external fertilization. During the breeding season, which usually coincides with warmer periods, males and females release their gametes (eggs and sperm) into the water column synchronously. This synchronization increases the chances of fertilization. The fertilized eggs develop into planktonic larvae known as pluteus, which float in the water column for several weeks before settling on the substrate and transforming into juveniles. This larval stage allows for wide dispersal of the species via ocean currents, contributing to its broad geographic distribution.

An interesting fact about Echinothrix calamaris is that, due to its long and sharp spines, it can cause painful injuries if handled without care. The spines are fragile and can easily break, becoming embedded in the skin. Although not venomous, the wounds caused by the spines can become infected, so direct contact with this urchin should be avoided. In addition, Echinothrix calamaris is considered an indicator species in coral reefs, as its abundance may reflect ecological imbalances, such as a decline in natural predators or algal overgrowth due to eutrophication.

Photos:

from

from